It’s a bit odd that Tom Baker claims that he came up with the idea of his Doctor offering people jelly babies considering that the motif appears in a couple of Patrick Troughton stories. The more obvious, more likely explanation is that Baker is just remembering it wrong. He’s a notoriously unreliable source on his own era. He worked very intensively on the show, doing multiple stories at once so they all melded together, and drank very intensively off it; he probably would have struggled to remember that sort of thing by 1979, let alone by 1992. Terrance Dicks is far better poised to have established jelly babies, seeing as he wrote a Troughton story, wrote Baker’s debut and edited The Three Doctors, in which Troughton makes a jelly baby joke. It’s even easy to speculate why Baker may remember doing so - The Face of Evil contains a wonderful jelly baby adlib Baker is justifiably prone to bragging about, and in The Invasion of Time clarifies Tom Baker’s favourite jelly babies are the Doctor’s favourites, too. But let’s assume he was telling the truth. Baker often says he didn’t watch the show before he got cast, though he occasionally mentions he saw a few episodes of Troughton’s era and liked the character. That’s not surprising - as soon as you are willing to recognise Baker as a trained actor doing a considered performance of a script rather than take literally the joke that they pulled him straight off the building site and added only a scarf, you can see Troughton’s influence. But there’s a deeper implication here - if he recognises jelly babies at all, and if they left enough of an impression on him that he associated the character with them, then this probably means that the Doctor performance he based his whole approach around was Troughton in The Dominators. And that’s a fun idea, since I don’t think it’s controversial to say that Troughton’s performance in The Dominators is the worst Troughton Doctor performance that still exists. Troughton’s performance on a good day is still a character acting performance rather than a leading-man performance or comic grotesque - the Doctor has become more central, but he’s still part of an ensemble. But The Dominators leaves him mugging in the spotlight, chewing the scenery to take the attention off the fact that it’s all made of polystyrene. He gurns his mediocre jokes (‘Oh my WORD!’), makes puerile adlibs (‘these little number-nine pills...’), howls and flails about while knocking things over (‘Whoaaaah!’). But worse than the desperation is the contempt. He’s so desperate to prove that he is slumming it in this trash that he actually acts it sarcastically, overacting, drawing out his comic timing, rolling his eyes and cracking adlibs that call attention to the story’s characterisation problems (“You got me there!”) without actually doing anything to smooth them over. It’s massively misjudged, since the story’s already self-mocking and absurdist, and because he’s saved worse scripts than The Dominators (Tomb of the Cybermen and The Web of Fear) by doing them properly. And I think Troughton was smart enough that he knew that. He hated the production conditions at the time, and so he went into sabotage-mode. Of course, that said, it’s not like his performance in The Dominators is bad, or anything. Even Troughton in a I-don’t-give-a-shit week is fun to watch - at least, compared to Pertwee on an I-don’t-give-a-shit-week. If you didn’t know Troughton on a good week, you wouldn’t know it was a bad week. You’d just assume that this was what the Doctor was like. And if Tom Baker’s main experience with the character was The Dominators, chances are he thought that too. Tom Baker’s Doctor brings a lot of new developments to the character, but one of the most significant is irony. His Doctor is self-aware in a way none of his predecessors are. He talks to himself, to the camera. He makes fun of bad acting in his own show, rolls his eyes at bad special effects, and indulges in both with a wink and a smirk at the ridiculousness. He watches his own performance with us as he plays it out, and laughs at it the whole time. Boiled down to its components, that’s not that different to what he’d seen Troughton doing in The Dominators - but for Baker, it’s an in-character irony, not an out-of-character one. He didn’t realise it was Troughton on an off-day - he assumed that’s just what the Doctor is like, just like he assumed the Doctor just always eats jelly babies. And so the contempt is absent. Instead of trying to make the show look like it’s beneath him, he lets himself get fully involved. And it turns out that involvement is very important for making the low-campiness of the show work. When Troughton clowns around in The Dominators, he’s being insincere. He seems to be saying, it’s a terrible show, and I shouldn’t be in it. But when Tom Baker clowns around, he’s doing a sincere performance of insincerity. He seems to be saying, this is the best show in the world, because I’m in it. The Dominators doesn't just create the basic character feel of the most iconic classic Doctor, though. It’s far more significant than that. For instance, it introduces the concept of an alien race with two hearts - at a time before the Time Lords were even established in the series, let alone their binary vascular system. Seems like an oddly specific thing to recycle - two hearts. Especially as, in the case of The Dominators, it’s a literalising of a metaphor, part of the story’s absurdism. ‘Two hearts and no brain’ was the idea, the old lefty-bashing cliché. Only both Dulcians and Time Lords do have brains - supposedly highly intelligent ones, with even utter racists like Rago praising the Dulcians’ intelligence - and the Time Lords don’t scan as a lefty caricature. Even before Robert Holmes (establisher of the two hearts) turns them into a House of Lords/Oxbridge dons/Catholic Church/Cold War-paranoia-era US Government mashup, they’re very conservative. They’re Lords. They’re a race of elderly white men in formal dress, whose main political belief is that they should leave things as they are (with them on the top). Holmes, cynical and anti-corruption, saw Terrance Dicks’ race of good non-interferers and sneakily gave them two hearts to remind us that, essentially, they’re the same as what the Dulcians were being criticised for six stories ago. And, anyway, is the Dulcians’ caricature really as simple as them being left-wing? They seem to spend all their time congratulating themselves for doing nothing about their big ideas (‘inaction is itself a course of action’) and getting mortally offended by semantics while missing the spirit of what is said (the lovely moment when Rago announces his intentions to murder them all and the councillor lectures him about ‘using that tone’). The problem isn’t that they’re pacifists - the Doctor says multiple times that he thinks their pacifist philosophy is noble - the problem is that they’re self-absorbed hashtag-activists (hilariously and absolutely unintentionally, they even spend all their time staring at tiny screens!), so up themselves that they think regurgitating their philosophy to a small echo chamber of people who already agree with them is a revolutionary act when people are dying and they have the direct opportunity to do something to stop it. The Dulcian politics are very generational, as well - old men who support inaction even when invaded by a pair of absolute losers with shitty robots, versus young protesters and marchers and revolutionaries who learn to overcome their prescriptive education and want to do something to change the world. Cully’s often interpreted as being hugely miscast in this regard, but I don’t think so - he appears about the right age to be Senex’s son, which he is, but most importantly it causes him to resemble the Doctor (especially since his two students are a brainless warrior boy and a girl who has been educated to have perfect fact recall). Before this, we assumed the Doctor was a wise old man amongst his people - if we think back to The Time Meddler, the Doctor expects to be treated like a senior and feels insecure about the Monk having a better TARDIS than him - but Cully leads us very nicely into the eventual revelation that the Doctor is more a prodigal son, a bratty little boy... a student activist. (In fact, later on, Holmes literally makes the Doctor a student activist in Carnival of Monsters.) But it’s not just that The Dominators sets up the entire structure of how Time Lord society is going to work before the Time Lords even show up - it’s got more to it than that. After all, it’s got one of the darkest, most cynical moments of all Who history in it, in its very first episode. We go inside a ship and see a late-middle-age academic - melodramatic and flaky but genuinely adventurous - with the personality of a much younger man, surrounded by dim but sexy teenagers. (He’s using his ship illegally, by the way - his two-hearted species wouldn’t let him travel but he’s doing it anyway.) His friends speculate about how dangerous or boring it’s going to be in the outside world while he checks the safety on the ship’s scanner, and he and his companions wonder out into the quarry-planet, and encounter short robots with funny voices - and they murder the teenagers before our eyes. And then we go inside the TARDIS. The Dominators starts by staging a stereotypical Doctor Who opening and ends it with everyone getting killed. And people think The Space Museum is a parody of Doctor Who. There’s obviously a lot of The Daleks in The Dominators - little gimmicky robot aliens, nuclear war, a pacifist race that has to be taught to fight again. All very intentional. There’d already been some catastrophically awful attempts at making ‘the new Daleks’, so presumably Lincoln and Haisman wanted to try repeating the same basic story again in the hope that it’d work just as well the second time. (And The Dominators is better than The Daleks, because it’s got jokes in it, and because it’s shorter, so there.) I don’t think ‘the Dominators’ is a bad name at all for a culture that is primarily based around dominating. It does sound a little bit like an American football team, but you’ve got those big shoulderpads involved, so that’s fine. It’s no worse a title than the largely unmocked term ‘Time Lord’. And there’s a certain level of honorific to their titles which I like - they refer to those above them as ‘Dominator’, to themselves or to those below by their titles (‘Navigator’ and ‘Probationer’). Are lady Dominators called Dominatrixes?

Are there lady Dominators? It’s interesting - you’ve got two Dominators in the entire story, both men, who hate each other; and you’ve got Quarks, who are coded as children. I’m not proposing that the Quarks are Rago and Toba’s children - that makes virtually no sense, fun as Rago and Toba are to ship (I’m not going to pretend I don’t). But there’s a compelling idea there. The Dominator empire is clearly a dying empire - stretched thin of resources, stretched thin of men. They can only afford two men to secure their vital new energy source, and they’re incompetents who hate each other. So they pad out the numbers with robot children - an artificial facsimile of a next generation, and as boy soldiers to fill the front lines, holding guns and doing what they’re told. I assume that some time after the Dominators attempted to blow up Dulkis, their empire progressively crumbled and in that weakness the Quarks overthrew the Dominators and went on to bother the Second Doctor and his grandchildren John and Gillian in all those comic strips where they did that. Just like on Dulkis, the generation try and keep things as they are, and their children try and change things, even if in this case they’re robot children.

1 Comment

Can't imagine there being many people here who don't already know about it, but I was a guest on the podcast Pex Lives! discussing The Macra Terror a little while ago. You can listen here!

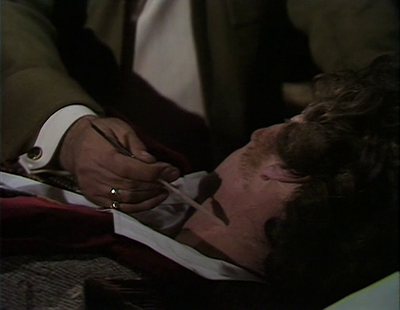

Later on in the story, Solon explains to Morbius that the reason he became obsessed with using the Doctor's head in the project is because, as a Time Lord, it would be more appropriate - he says he likes the idea of having a representative of the culture that ended Morbius's life being the literal figurehead for Morbius's reign. But Solon's reaction to the Doctor's head happened before he found out that the Doctor was a Time Lord, not after - when he opens the door, he's eagerly anticipating 'human' visitors and he only realises what the Doctor is after the Doctor starts chatting about all the different heads he's had. The order in which Solon finds out the Doctor is a Time Lord and in which he falls in love with the Doctor's face changes the entire story. It goes from being a story about a scientist seeking appropriate organs for his work, to being a story about a scientist who wants to use Tom Baker in a thing he's doing because he's the most gorgeous man he's ever seen. There's been stories before this where characters found the Doctor handsome (Polly, seeing the Doctor after his makeover in "The Macra Terror") or dashing (Liz giggling about the Doctor flirting with her in "Spearhead from Space") but never before have we been presented with a character who unambiguously finds the Doctor beautiful. Of course, this Doctor isn't one of the most unambiguously beautiful ones. And the things about him that are commonly admired don't get any focus here - his sparkle and his smile get little attention and his famous voice goes without comment, save for a scene where Solon isn't present which places great emphasis on the Doctor saying the word 'Popocatepetl' simply for the sheer pleasure of hearing Tom Baker say the word 'Popocatepetl'. In fact, he spends much of the story unconscious. But his expression doesn't even appear pained or vacant in most of his unconsciousness scenes - instead he wears a proud, beatific expression like a carved knight dreaming on his own coffin. The charitable description of this Doctor's face is 'Classical', and with his eyes and mouth closed that image takes over - scenes in which he camouflages himself amongst Solon's Classical-styled sculptures do a lot to emphasise this way of viewing him. In fact, the more common and less charitable description is outright rejected - the giant-toothed, swivel-eyed Mutt head and Morbius's protruding eyes are there only to be images that the Doctor is not, so inferior as to be beneath consideration. It would be easy to portray Solon's opinions of the Doctor as laughable - much of the rest of the story portrays Solon as laughable - but instead the story draws us into his way of thinking by showing it to us. The story distances us from Solon by making him ridiculous, and yet pulls us into him when we end up sharing the same visual pleasure, and the effect is a deliciously creepy sense of guilt by association. For it's really unusual just how much we end up relating to Solon in the story considering he's both the antagonist and an almost comically horrible person. The slightly absurdist tone is part of what makes him as relateable as he is - he's fallible, makes obvious mistakes, driven by emotion, and we can all understand that because we've all been that person. While he's subordinate to Sarah in terms of an audience insert, losing his viewpoint status when she is present, he is superior to the Doctor, who is only used as viewpoint in his altercations with the Sisterhood. This Doctor is one of the most relateable Doctors, the Fourth Wall Doctor who didn't need a companion and derailed his own show by becoming his own audience, and yet he is presented in this story mostly as an object to view, with the exception of when he's facing a group of women defined by their inability to sense him. And yet even the Sisterhood, who can't sense the Doctor and Morbius because of their Time Lord minds, can scry for him. With the effort of her Sisters, Maren is able to see an image of him, viewing him on a screen much like the audience is doing through her perspective. And the vision she sees of him is a shot of his head. The very first thing that we see in "The Brain of Morbius" is a stylised image of the TARDIS emerging from a whirling psychedelic pattern, which resolves into an image of the Doctor's head. He is wearing a blank expression, and his face is lit with symmetric lights that make his features seem inaccessible, reducing them to geometric shapes like the light show he emerged from. The basic truism goes - introducing a character with a body part makes the audience see them as an object; introducing a character with a shot of their face makes the audience relate to them as a character with feelings. But the Doctor's head is presented as just one object in a list of objects. This is the TARDIS; this is the logo; this is the disembodied head of the Doctor. The Hinchcliffe era, the era The Brain of Morbius belongs to, comes at a time in Doctor Who history where it's beginning to self-mythologise. Regeneration of the Doctor has happened three times (or, at least as far as The Brain of Morbius is concerned, that the audience knows about); like the Rule of Three in folk tales, three times is enough times for it to develop from being a shock twist to an ongoing pattern, a feature of the show, a selling point. One of the earliest scenes in the story is set up to remind us of this - immediately after the scene where Solon falls in love with the Doctor's head, the Doctor does some of his trademark Fourth-walling when he reminds us that 'a lot of people seemed to like' his last head, referring to its success with fans as much as with Jo Grant and Benton. Except he doesn't actually use the word 'head' when talking about it - he refers to both his previous head and his current head as 'models', as if he's merely changed his car. When the show itself treats the head of the Doctor as both instantly striking and fragmentable, the physical centre of the show and focus of its popularity - when the Doctor himself considers his head to be an interchangeable device for carrying his brain around in - when Solon is the audience insert character for much of the story - why do we still make the old fanboy jokes about why Solon didn't just transplant Morbius's brain into the Doctor's whole body? It's worth emphasising just how little interest Solon actually has in the Doctor's body. In theory, Solon plans to violate it, and the gothic horror rape allusions used in various previous Tom Baker stories (a soldier sadistically torturing a female POW by forcing her to hallucinate a snake crawling up her leg?) could easily appear here if that was the story being told. Solon's given more than enough opportunity to creepily touch the Doctor's lips or lick him and or whatever - he certainly would have done in a lesser story, which would have used it to cheaply indicate that we are supposed to hate him for being depraved - but the closest he comes is running fingers over his chin at arm's length with the expression of a man who can't quite believe he's allowed to touch the exhibit at the museum. Instead his appreciation of the Doctor is based around Solon's aestheticism, the part of him that makes sculpture and talks about letting wine breathe. When surgically examining the Doctor in the first episode, the tools he uses aren't medical-fetish/phobia shiny metal; he listens to the Doctor's heart with a gorgeous turned wooden stethoscope, and when he takes the scalpel its carved mother-of-pearl handle glints in his heavily ringed hands before he runs that end very gently over the Doctor's throat, holding it like you would a feather rather than a knife. The tools might be intended eventually to invade but they never do, instead passing over the Doctor like a gaze. Solon's obsession with performing the operation perfectly is a means of honouring the person he wants to put inside the superb head - if Solon hadn't cared so much about decapitating a man in a manner he thought beautiful, the Doctor's headless corpse would be stinking up the laboratory before the end of the first episode. Solon is less a mad scientist, and more a mad artist. The only character from where body desire appears is Morbius - furious about his own lost looks, dysphoric about his current body, and far too responsive to the Doctor's insults. The Doctor describes the mindbending contest as 'Time Lord wrestling', which has certain connotations considering the Greek sculptures in the set design that you wouldn't get if he'd called it 'Time Lord arm-wrestling'. But even when Morbius overpowers the Doctor and starts crowing about how he's violating him, all he appears to be doing from the audience's perspective is observing the images of his heads - and at the same time we are shown that he is looking at parts of the Doctor so secret and personal that not even we know about them, that (played as they are by production members) lurk slightly on the wrong side of the fourth wall. This Doctor is one of the most active Doctors, the one famous for bending stories around his will to the point of derailing a show that was supposed to be about him anyway. And yet his only option in the fight against Morbius is to submit to his gaze, to allow his self to be destroyed through the viewing of his head. But if the actors who played the Morbius Doctors are relevant, it has to be relevant that it's a Tom Baker story - the actor who most used the Doctor's face as a means of allowing his self to be lost. The scene where the Doctor has been drugged but first appears to be just drunk is clearly playing with actor personality rather than Doctor (the precedent, the Doctor's enthusiasm about the pub in The Android Invasion, was a Baker rewrite) - so if there's already one biographical idea in there, maybe all this face-peering draws from Baker's own quirk. Baker suggests it developed as a result of spending years in an environment where he was religiously forbidden from looking at the faces of others in the name of modesty; he has written about falling in love with beautiful male fingers and necks, losing perception of other bodies as anything more than individual parts, becoming desperately and immediately infatuated with another novice simply because he inadvertently looked up and saw his magnificent head. Maybe that's why Solon, living in a secluded, all-male cathedral-like environment as part of his religious devotion, was so struck by the Doctor; piecing together ideal bodies from disconnected limbs, he was able to finally complete the image with a face, and struggled and failed to put his faceless God in it.

No wonder Morbius tells Solon that he doesn't want the face of a Time Lord, and to instead forego getting a face altogether. (I love how much of an unhappy, miserable, jealous family the three castle-dwellers are.) In a setting where all characters are seeking physical completion and stability - even the castle he lives inhas ball-and-socket buttresses, suggesting transience - he chooses to remain incomplete, foregoing an organ that allows others to see his thoughts in favour of one that shows only his brain. Those aren't his faces during the mindbending, and in fact the only time we do see his face it's when the drunk-drugged Doctor finally recognises the statue - which causes the Doctor's dream in which he feels a direct connection to Morbius's thoughts. So Morbius fails because he refuses to submit to allow himself to be seen. Notice how Sarah shows no fear of Morbius while blinded, treating him as an equal and even a potential ally, and only screams when her vision comes back and she sees that he still cannot be seen! It's appropriate that the faceless Morbius is damaged by 'static buildup', too - robbed of a face to allow him to express externally, his thoughts causes energy to build up internally until it damages him. So even if Solon's fixation on the Doctor's head and Morbius's fixation on the Doctor's faces is objectifying, it doesn't mean our gazing at him is. After all, even if this Fourth-wall Doctor knows where the camera is, he still can't see us watching him at home. Our gaze at him isn't us communicating with him - it's allowing him to communicate with us. Without us watching none of his adventures would happen, because he is performing for us, so it's because we watch the Doctor's face that the Doctor has an identity at all. Without the immodesty of a face, he would sink into the depersonalised introspection of Morbius. This post was originally made on my otherwise dead Dreamthingy on the 15th January 2015.

I Oh, Doctor, honey, you and the Brigadier are never going to work. You go on about how you need him, but you aren't being honest - you've got no need for money or material possessions and even without the car you've got access to any form of public transport on Earth. You can't convince me that a man of your charm and intelligence, with your history of being able to show up anywhere you like and become the centre of the world, couldn't talk your way into a job interview for anyone else. You've got your house and your car now, and even as much as you love them they don't tie you down as scarcity does not exist in your world. You don't really think you need him, you think he needs you. You think he needs you to stop him. (You're not yet at a stage in your life where you need others to stop you - you've only really done one cold judgmental genocide and turned yourself in to be regenerated in the next story but one, as if you knew it meant you'd gone too far.) Remember when you saw him murdering thousands of people out of racism, committing a genocide against a race he refused to try to understand, only seeing their different skin colour and how much their radicals hated you and bombing them while they slept - you knew he would do it, you asked him twice not to, you knew he was going to do it and yet you still saw him and your voice quaked with rage as you accused him of murder. And you went back to work the next story. You made a dark comment to Liz about how the Brigadier must be out of people to kill, but you went back to work the next story. Hell, both you and Liz have different haircuts in the next story, so maybe some time did pass, some time and anguish and reconciliation, but why would you go back to him for the next story at all? You need to realise that you aren't going to change him, he is too stupid to change. Forty/howevermany years from now, when you're allowed to actually kiss your companions instead of just having relationshippy resonance in the way your platonic allegiences go, you'll be surrounded by girls who are cleverer than you by virtue of insight - 'but, Doctor, I believe you can save everyone and you don't have to do this terrible thing' girls. You've had some of those already in the past, though they were a little less obvious about it. Liz is clever, and you treat her like an equal, with great fondness and respect, but the Brigadier is stupid. His main contributions are telling people to do what they're already doing anyway, murdering people and wasting bullets shooting at invincible and friendly aliens in astronaut costumes. Doctor, honey, he's handsome, and he bought you an expensive gift, but some people are just toxic. He's made it clear that he'll continue acting in the same way he does no matter what you do to stop him. These are irreconcilable differences, and you need to dump him. II Oh, Doctor, you got it so close. You came so close to walking out on him and you ended up getting dumped yourself - literally dumped, stuck in the UNIT rubbish dump seconds into the future, after attempting to storm out with a faulty TARDIS. Then you apologised to him because you didn't want to go back and dig it out. You could have done better. There were a lot of emotions at play. You'd failed to save Nazi alternate universe versions of your friends from drowning in fire, which has got to make you feel a little bit stressed, but that probably wasn't why you snapped at him. In fact, before then, you'd even slipped up and called him 'Brigade Leader', the title of his fascist version - you genuinely fell to the most clichéd slipup of faithless lovers. The Brigade Leader was not much of a better catch - he beat you, tortured you, threatened to shoot you even though he knew you were unable to save him, and (by your stated opinion) not as handsome without the moustache - but he left an impression on you, and I think it was probably down to his vulnerability. You were able to break him, you see. Your Brigadier observes, acts, and never reacts; the Brigade Leader emotes, panics, lashes out. Surrounded by the trappings of absolute power, he felt secure enough to show the little boy playing at being a soldier that you always suspected he is, but that he never, ever trusts you with. And, look at that. You got him to change. The Brigade Leader would be better for you if he wasn't stuck in an alternate universe drowning in magma while hairy fire zombies tear people to pieces in the background. So what you do is you literally dump yourself and literally get back together with him after literally two seconds by convincing him you need him. You think you've had it confirmed that he can change, but actually it's the opposite. Change is impossible. You can do better. III Wow, Doctor, is that you? You look amazing! You're smiling so much more, and I love the cardigan and the big pockets and the shoes and is that a new hair colour? Oh my god, I'm so glad you finally dumped him. The lines have gone from your face. Even your voice sounds stronger. I suppose there has to be some significance to the way you finally managed to get out of it. When you tried to dump him in dramatics, in anger and inferno, you ended up tossing yourself into the trash. So instead you just left with boredom, left him without a word positive or negative (except for a rare-for-you moment of vulnerability when you punched a brick while almost tearfully telling Sarah Jane that you won't won't won't go on like this), without a journalist and without a doctor and without a Doctor, running off to find something fun to do leaving him to stand around waiting for you to come back. With a booking for one of those awful dinner parties he used to take you to, the ones which are always just an excuse to show off how much cooler and more powerful his friends are than yours. Two major things happened around the time you finally cut him out of your life. The first thing, on shallow inspection, just seems like more of the same; more shooting at beautiful things he doesn't understand. But there's more to it than that - he wasn't satisfying you any more. Never before have his ineffectual bullets and macho military action been so sexual, so impotent; we cut from you telling your new friend Harry (who is much better for you than the Brigadier, did I say?) about the Freudian theory of 'compensation' to the Brigadier firing a huge, pink-tipped gun from crotch level while grunting about giving the killer robot something. But the size is soon dwarfed, because the robot gets hit by the gun and immediately grows so much bigger, while the Brigadier looks on in despair at his own limp tool. Never before has the Brigadier been shown to be so unsatisfying. You put the robot back to normal size by chucking a cold shower over it, but even the girthy cannons on the Brigadier's tanks looked like toys in comparison. No wonder you were bored. The second thing that happened is a little more beautiful. Didn't I tell you you couldn't change him? You never managed. You never changed him. In the end the answer was give yourself a little time alone to think, to face your fears, and then to let everything you learned tear you apart on the inside until it changed you. The hurt's going to fade, and you're going to remember and miss the good times - you're going to look upon him later in life as a loyal friend instead of as the genocidal, militaristic shit who committed a genocide and got away with it scot-free while simultaneously ruining everything you tried to accomplish. Maybe in the near future, when you're hurting for a friend and you're drowning in violence for a week, you might find yourself seeking out a soldier again who you have to convince not to kill things she doesn't understand - but do yourself a favour and make sure she's someone who's willing to change. There might have been a moral in this post about how other people than you, Doctor, should have their relationships, but if there is one I have no idea what it is. In Tomb of the Cybermen, the other Doctor Who story where the Cybermen come out of their tombs and an over-the-top villainess with a funny accent has given them the means of doing it in the hope of gaining control of them as an army, the first character we see on screen is a character named Toberman. As you can probably guess from how he's presented to us in that clip with special emphasis given to his presence, Toberman is sort of the hero in the story. He spends most of the story working in servitude to commands given to him by the other characters, with his fighting skills being his main asset - a soldier, you could say. He is able to pass into the world of the dead by being the only person strong enough to open the doors to the tomb, and when the villains cause the Cybermen to emerge, he is converted into one. The Doctor appeals to his humanity, and he turns against the Cybermen, killing them before sacrificing himself to save the Doctor.

This all sounds rather better than it actually is. Toberman may be sort of the hero of the story, but in the most racist way people still seriously defend. His characteristics are that he virtually never speaks, is subservient to the other characters, super-strong, temperamental, proud and stupid. "He was supposed to be deaf," say certain fans, waving their Target novelisations at you, "you shouldn't criticise, you should celebrate the show for having a disabled black man in it as a hero." This is a terrible argument, because his 'deafness' only exists to characterise him as having no words or ways of understanding the world of his own, and because Toberman's alleged deafness is never mentioned or so much as implied in the script or acting, ever. Toberman doesn't just exist in a world without a means of expression, or perception, or goals or dreams or character. He even exists in a world without love. Kaftan, his boss and the person he's the closest to in the story, doesn't care about him at all except as a body. The Doctor, a hero representing love and freedom, makes his appeals but it's only to use him for his own ends himself - bonus points for making the mega-racist allegorical implication that he (and black masculinity itself) only became enslaved through his own choice! And when Toberman sacrifices himself, it isn't done out of love for anyone or anything else - Cyberconversion stripped him from all apparent emotions except for a desire to kill the Cybermen. His scene of sacrifice is painful to watch, because he's so out of it that doesn't even seem to be aware that he's making the decision to die, making it even meaningless. Despite this, Tomb of the Cybermen is still taken seriously. Neil Gaiman said it was his favourite story, while Matt Smith famously called up Moffat in the middle of the night to squeal about how good it was after watching it. There's no other racism in Doctor Who so extreme that simply never gets commented on. Talons of Weng-Chiang, in which the only noble villain is a white man in yellowface and the Doctor joins in with the side characters in making racist jokes about him is roundly derided for the racism even as people praise the production values, the dialogue and Tom Baker showing off a bit of acting range in it. The Celestial Toymaker, which has a white man in Chinese dress as the villain and uses an older version of Eenie-meenie-miney-mo, is only even remembered for being 'that Doctor Who story with the n-word in it', and its 00s sequel goes out of its way to have a scene in which the Doctor yells at the villain for mindlessly appropriating cultures he doesn't respect. But Tomb of the Cybermen is still thought of as a highlight of Troughton's era, and everyone seems to just forget Toberman exists. I don't think we should. We need to remember just how bad this show could get, otherwise we'll never really understand how to improve. And the show has improved, it has gone out of its way to improve as much as it can. But in its constant nods to and references to its past, you get stories like Nightmare in Silver that reference Tomb of the Cybermen, without acknowledging the fact that the hero of the story is a really insulting stereotype of a black man with no agency of his own. I can't say I was a huge fan of Danny Pink's character. He and Clara seemed to have little reason to want to be together and both were thoroughly shitty to each other, although for different reasons and in different ways. And then Danny crossed through the threshhold into the land of the dead, and the hammy villainess made the Cybermen come out of their tombs, and Danny got Cyberconverted, and placed against his will into the role of Toberman. We never doubt Danny's intelligence or fundamental good nature. He owns his mistakes and makes his own decisions. Even when he lives in a world without words or emotion, his decision to sacrifice himself is made from the emotions he felt when he still had them. It's so easy for the show to look back at its own past and pat itself on the back, indulge in the behind-the-sofa moments and the funny lines everyone loves. But it was brave of itself to risk reminding us of Toberman. And good of us to do so by spending a whole series reinventing and saving Toberman by making him a person, a human being, with his own outlook on the world and his own life, instead of the hollow shell he was. And long overdue. And imperfect. And needed. This essay was originally posted on my otherwise defunct Dreamwidth on 17th October 2014.

I hate The Web of Fear. It's not the worst Doctor Who story I've watched on a structural level (The Celestial Toymaker can't be beaten here, though it's definitely one of the worst) or the one that has pissed me off the most (Day of the Moon, Angels Take Manhattan, Let's Kill Hitler) or the most racist (Tomb of the Cybermen can fuck off), but by god, I hate it. I hate it and I hate the fact that most Who fans take it seriously just because it was missing for years and has the Brigadier in it. I hate the fact that the fanbase consensus is that the slow-motion Mornington Crescent-em-up The Web of Fear is a classic and hate things like The Gunfighters and The Underwater Menace for being quirky and including singing. (Classic Doctor Who fandom doesn't really seem to like the comedy stories as much as you'd expect. It does seem to be based around the idea that Doctor Who would be better if it was more like Star Trek, or even Star Wars. People love City of Death, all right, but at the time of broadcast people criticised it for being silly - and then the writer went on to become incredibly famous for creating a series of really funny books that everyone loves, so now it's considered genius. Of course, this is bollocks - there's no reason why good comedy is any lower than good horror - and it's especially cruel to judge comedy in a series where the most obvious appeal is that the main character is an eccentric who pulls googly-eyed faces and clowns around and defeats humourless racist robots by being funnier than everyone else in the room. Say what you like about NuWho fandom, but at least most of the Tennant-GIF-and-fez-brigade understand that jokes need to be there, and that it's good having fun.) The first couple of episodes of The Web of Fear aren't really that much worse than anything, and even have at least two good scenes. There's a nicely obvious Strong Female Character bit where Miss Travers tells a sexist jerk asking her how she got her job, "When I was a little girl, I thought I would like to become a scientist. So I became a scientist", and an oddly warm part where a couple of UNIT soldiers speculate ignorantly about whether the London Underground-invading robot yeti shooting webs out of guns (yes, I know, more about this later) are sent by the Russians, lacking the knowledge, interest and power needed to ever get an answer. But then the third episode tosses in the Brigadier and then he needs to have the plot explained to him for the entire episode, and so nothing happens in it, and then we're far beyond the point of no return. The Great Intelligence - one of those villains Doctor Who fandom fetishises because it looks a bit like something HP Lovecraft would create - claims it has no interest in revenge ("a very human emotion") and immediately explains to the Doctor that it's going to get revenge on him. I think this is deliberate - I think the Great Intelligence is a cosmic manchild, neither as powerful nor as inhuman as it pretends to be. The Great Intelligence can possess people but needs to construct machines in order to get anything done, and wants to steal the Doctor's brain out of what is probably just a wounded ego. It's the most insecure eldritch horror I think I've ever encountered. It delivers these threats to the Doctor through the possessed mouth of Professor Travers, an old ally of the Doctor from the story The Abominable Snowman and one of the most likeable characters in the story, and the writers flat out forget to have the Doctor appear at all upset about the fact that the Great Intelligence has hollowed out his friend's mind - he just reacts with Doctorish indignation, and some frowning and companion homoeroticism on account of those being his gimmicks in this incarnation. Say what you like about Moffat, but at least he bothered to have the Doctor be properly upset about Walter Simeon's possession. The characterisation of the Great Intelligence is actually very consistent, and you should not listen to anyone saying otherwise. I think I did mention the fact that the monsters in the story are London Underground-infesting robot Yeti with glowing eyes and handheld smoke pistols, ridiculous in clawlike hands, a child with a latex halloween glove and a spud gun. This smoke coalesces into spiderweb-like structures that block radio waves and control people's minds and do whatever they're supposed to at that point in the story. They are controlled by floating metal spheres, or by manipulating wooden carvings of Yeti which act as homing devices. If this sounds like a pile of completely random traits I'm pulling out of a stovepipe hat, that's exactly what it's like. And that is why The Web of Fear completely falls for me. What is a Yeti? A miserable pile of spooky traits, shoved together with no rhyme or reason. The Yeti make no sense, and there is no context to them. The Yeti are not a metaphor. The Daleks are a metaphor for fascism and paranoia. They wall themselves off from a world they're frightened of and do not seek to understand and then scream threats and bigotry at it from behind an expressionless luminous screen, like you or someone you know is probably doing in a comment section right now. They are Nazis in The Dalek Invasion of Earth, Communist agents in Power of the Daleks, dark alchemies and magic formed from the evil side of human nature in Evil of the Daleks, and Dalekmania-induced mascots in The Chase, but even if what they mean changes between stories their meaning is always there and it is always significant. The Yeti, in their first story, did represent something. The Doctor defends a Buddhist monastery from suddenly violent native wildlife which turns out to be not native at all, but robots built to look like Yeti. An inorganic but somehow thinking being, metal spheres and glass, has already subverted the priest (a five hundred year old being of great wisdom and quasi-magical powers) and is using his religious influence to shield itself. In the climax, the giant pyramid mountains appear illuminated and glassy like the pyramid structure of the Intelligence, the land itself becoming the evil influence; and while the Doctor teaches the monks to go against the teachings which caused the toxicity to take hold, he also has the monks teach Victoria a prayer in order to help her resist its influence. In this world, the Yeti are technological encroachment on a traditional way of life, a creation of a deeper cultural corruption that prizes power more than spirituality. But what are they in The Web of Fear? They're just there because... the Yeti are fun. They are just there to be monsters, gain a bunch of other arbitrary traits and mean nothing. There is nothing that would change in the plot if you replaced the Great Intelligence with WOTAN and the Yeti with the War Machines - in fact, that'd improve it, since the Machines are a product of the future promised by 1960s London. Or replaced the GI with the Animus and the Yeti with the Zarbi - this would also work better, since the Animus was at least established to manipulate the world around it with webs. (There was a First Doctor comic with Zarbi invading the London Underground, actually. The Zarbi walked on six bug legs instead of two obviously human ones, though, and the writer seemed to think that the First Doctor's gimmick of calling Ian slightly incorrect names was something he did all the time instead of when he was trying to annoy Ian.) A monster that means nothing is no monster, less than a monster. It makes the story less than a story, chokes understanding out of it. Like that stupid orange clam monster that Harry steps in around the late middle of Genesis of the Daleks for no reason other than to make the plot worse, the Yeti are an impediment to the story's own theme. I've watched a lot of bad Doctor Who but The Web of Fear is the first one that actually means nothing. The litmus test for whether a monster means anything is to remove it from the story and look at what is left behind. Have a go, it's like a game. Take the Yeti from The Web of Fear and you're left with a story about the London Underground getting cunked up, something thoroughly nothing to do with the Yeti. But if you take the Daleks (and the clams, I suppose) out of Genesis of the Daleks what you're left with is a bunch of racist politicians who have already decided that terrible decisions must be made to determine their own survival, while the Doctor gets squeamish over whether to stop them in case his own view of how things should be is as megalomaniacal as theirs. Nothing unexpected there, but then I tried doing it to The Macra Terror. People seem to see The Macra Terror as a generic runaround in a quirky setting with some fun Delia Derbyshire music, but take out the giant crab monsters hypnotising a holiday camp planet and what you get is - Ben, a young man, realises his apparently happy world is one where people have to work themselves to death in dehumanising jobs for no benefit to anybody, with the sole thing to look up to being the occasional week in Butlin's. He eventually comes to believe in this world until his countercultural friend reminds him what life is really about. And suddenly, Gridlock makes sense - it's a fairly common opinion in Doctor Who fandom that the Macra should not have been used in Gridlock because their personalities are so different, much like how the new series ruined the Great Intelligence by bringing him back explicitly and openly obsessed with revenge instead of hiding it with a veneer of hipster irony. This has decent reasoning behind it - the Macra go from being hyperintelligent spacefarers to speechless animals, although they still share an interest in feeding on toxic gas. But, crucially, what the Macra represent is the same. The people in Gridlock are lovely, intelligent, creative and different individuals literally trapped on their commute to work all their lives, with only their decorated homes, chatting with their friends and singing hymns to keep them going. The fundamental horror in the lives of the colonists and the lives of the New New Yorkers is the same, and, so, so is the monster. This is how watching bad television can teach you more than good television, at least if all you care about is crabs. |

A Doctor Who blog by Holly Boson. Assorted thoughts and activities.

Archives

May 2015

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed